Our Context

Care population

- The population of aged 18 years and under is 1.2 million

- 6,054 and spent time in the care of the state or approved child and family social service between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023.

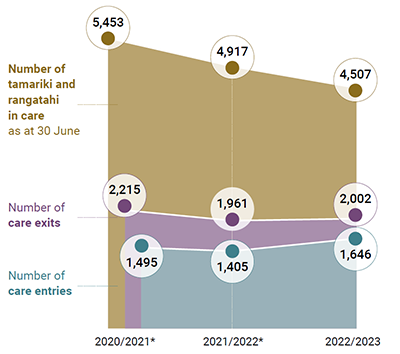

- 4,507 tamariki and rangatahi were in the care of the state or approved child and family social service as at 30 June 2023.

Care entries and exits

Care entries and exits

Care entries and exits

**The number of tamariki and rangatahi in care in 2020 and 2021 differ from our previous reports, because of the inclusion of number in custody under warrants. Oranga Tamariki revised the number of care entries and care exits following publication of our 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 reports.

The number of tamariki and rangatahi in care has decreased over the last three years of reporting. The decrease this year is proportionally smaller than we saw for the previous reporting period.

This decrease does not mean that fewer tamariki and rangatahi are entering care. The number entering care has increased since 2020/2021, but the number exiting care has remained higher, resulting in a lower number of tamariki and rangatahi in care as at 30 June 2023 compared with previous years.

Age

Age

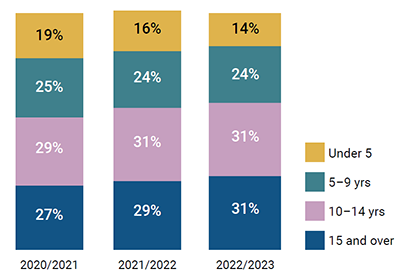

Over the last three years, the average age of tamariki and rangatahi in care has increased. The proportion aged over 15 has steadily grown, while the proportion under five has steadily decreased.

This may suggest that the increasing numbers of tamariki exiting care are from younger age groups and that fewer under-fives are entering care, while older tamariki and rangatahi are more likely to remain in care until they transition to adulthood.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity is the ethnic group or groups a person identifies with or has a sense of belonging to. A person can belong to more than one ethnic group. The ethnicities that tamariki and rangatahi identify as are:

| European | Māori | Asian | Pacific peoples | MELAA* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population under 18 (%) | 66% | 27% | 19% | 15% | 2% |

| Tamariki and rangatahi in care (%) | 48% | 69% | 3% | 17% | 2% |

*Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African

Tamariki and rangatahi with a known disability

Tamariki and rangatahi in care are more than twice as likely to have a disability than the general population, although this is still possibly underrepresented.

Gender

Custody Agency

Over the course of 2022/2023, 6,054 tamariki and rangatahi spent time in care. They were in the custody of:

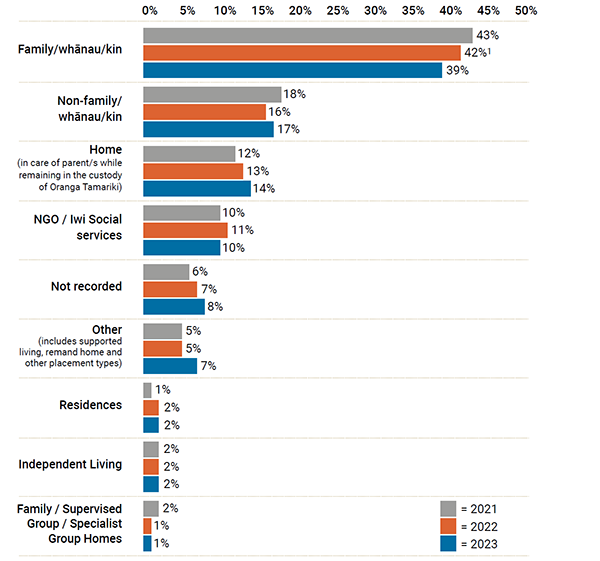

Placement types as at 30 June

Placement types as at 30 June

Placement types as at 30 June

Over three years, the proportion of tamariki and rangatahi in care placements has decreased from 43 percent to 39 percent, though it remains the most common placement type. The proportion of tamariki and rangatahi in nonkin caregiver placements remains similar. The proportion of tamariki and rangatahi at home in the care of parents (but under custody orders) increased from 12 percent to 14 percent.

1 The 42% recorded as being in family/whānau/kin placement in 2021/2022 is an update on the 38% recorded in our 2021/2022 report.

Duration in care and care entries

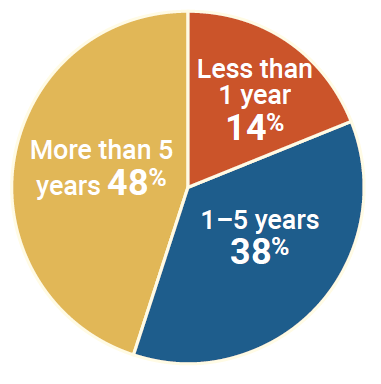

Tamariki and rangatahi under care and protection orders during the reporting period had been in care for an average of five years over the course of their life.

Seventeen percent of tamariki and rangatahi who were in care during the reporting period, had been in care before.

Tamariki and rangatahi in care % by duration in care

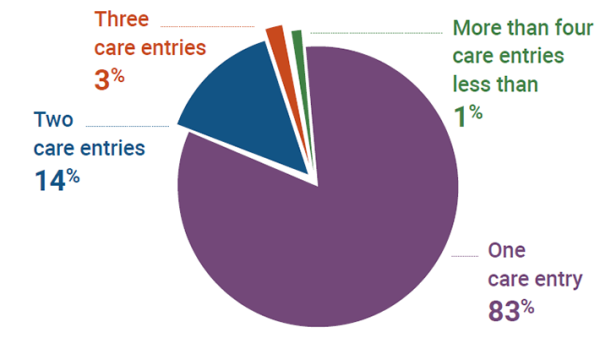

Number of care entries over time

Change in key relationships

When we spoke to tamariki and rangatahi during our monitoring visits, we heard that their relationships with their caregivers and social workers are really important.

We looked at how many caregivers and social workers tamariki and rangatahi have had during their time in care.

Tamariki and rangatahi that have experienced a change of caregiver

Almost three-quarters (74%) of tamariki and rangatahi have changed caregivers at least once during their time in care.

Older tamariki and rangatahi are more likely to have changed caregiver during their time in care than younger tamariki. Even among those who had been in care for less than one year, we found that rangatahi over 15 had the highest number of caregivers.

A change in caregiver is common even among under-fives; almost half had had more than one caregiver. Our analysis found the average number of caregivers for under fives to be consistent regardless of how long they have been in care, which may suggest these changes of caregiver tend to happen in the early stages of their time in care.

More than 1 Caregiver

51%Under 5 75%5-9 years 77%10-14 years 82%15 and over| Average number of caregivers | |

|---|---|

| 2020/2021 | 3 |

| 2021/2022 | 4 |

| 2022/2023 | 4 |

On average, tamariki have had four caregivers during their time in care, although this is inflated by a few outlying cases. This is consistent with the previous reporting period.

Changing caregivers

This graph shows how many tamariki and rangatahi change caregivers during their time in care.

| One caregiver | Two caregivers | Three caregivers | More than three caregivers | Not recorded | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 5 years old | 43% | 32% | 12% | 7% | 7% |

| 5-9 years | 24% | 27% | 19% | 29% | 1% |

| 10-14 years | 20% | 16% | 16% | 45% | 3% |

| 15 and over | 15% | 14% | 12% | 56% | 3% |

Changing social workers

The number of social workers increases as the age of the tamariki or rangatahi increases:

- The majority (61 percent) of tamariki under five years of age have had between two and five social workers over their time in care.

- In contrast, the majority (51 percent) of rangatahi over 15 years of age have had between 10 and 20 social workers during their time in care. A further 10 percent have had more than 20 social workers.

| One social worker | Two-five social workers | six-ten social workers | 11-20 social workers | More than 20 social workers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 5 years old | 4% | 61% | 32% | 3% | |

| 5-9 years | 0.5% | 18% | 55% | 27% | 0.4% |

| 10-14 years | 0.5% | 10% | 33% | 51% | 5% |

| 15 and over | 1% | 14% | 23% | 51% | 10% |

| Average number of social workers | |

|---|---|

| 2020/2021 | 9 |

| 2021/2022 | 10 |

| 2022/2023 | 10 |

Abuse of

Abuse of tamariki, both historically and presently, continues to be a significant issue within New Zealand. During this reporting period, the chief executives of six government agencies1 commissioned an independent cross-agency review of child abuse following the murder of five-year-old Malachi Subecz by his carer. The review, completed by Dame Karen Poutasi, was published in November 2022. Although Malachi wasn’t in the care of Oranga Tamariki, it identified five critical gaps within the children’s sector.

Dame Poutasi’s report made recommendations for change, including a final recommendation for the Independent Children’s Monitor to review the recommendations after 12 months. We have been working with agencies across government to understand the changes they are implementing to address the gaps and recommendations identified by Dame Poutasi to make Aotearoa New Zealand safer for all tamariki. A report on our findings from this review will be published in mid-2024.

In our chapter on Aroha, we report more specifically on how Oranga Tamariki has responded to allegations of abuse to tamariki and in care over this reporting period. Despite improvements in some areas compared with previous years, many tamariki and rangatahi continue to experience abuse after coming into care. Tamariki and rangatahi who return home, but remain in custody, continue to be overrepresented. These statistics, combined with hearing from parents that they didn’t always have the right services and support in place to make the return home successful, led us to publish an in-depth report Returning Home From Care.2 Our report found that polices, practices and support from across the social sector is not yet consistently in place to help tamariki and to make a successful return home, and thereby reduce the likelihood of further harm.

Oranga Tamariki Action Plan

The Oranga Tamariki Action Plan (OTAP) was published at the start of this reporting period.3 OTAP is a statutory requirement under the Children’s Act 2014. It sets out how children’s agency4 chief executives will work together to improve outcomes for tamariki and rangatahi “of interest” to Oranga Tamariki. Tamariki and rangatahi ”of interest” are those at risk of coming into care, those in care, and those who have transitioned out of care up to the age of 25 years.

OTAP includes short- and long-term actions to support tamariki, rangatahi and whānau, and to enable government agencies to work together more effectively. Some actions focus on better understanding the needs of tamariki, rangatahi and whānau, and others on improved data and monitoring. The first action is for children’s agency chief executives to clarify expectations to frontline decision-makers and operational staff of the requirement to meet the needs of tamariki, rangatahi and whānau involved with Oranga Tamariki.

Completed work under OTAP includes in-depth needs assessments on housing, primary health, mental health and the health needs of tamariki and rangatahi transitioning out of care. A May 2023 Cabinet paper on implementation states that some changes can be expected from the first tranche of OTAP delivery.5 These changes include a different experience for rangatahi in care through increased options for support into housing and other housing options when they transition from care. They also include and improved access to health and education supports for tamariki and rangatahi in care.

The in-depth assessments acknowledge that government agencies have a higher duty of care: “By taking these children and young people into care, …the State has accepted a higher positive obligation, which is to provide day-to-day care of the child or young person.6” Despite this, the primary health needs assessment acknowledges that “children and young people in care have arguably the poorest health and wellbeing of any population in Aotearoa New Zealand and fewer protective factors for health.7 The mental health needs assessment recognises “evidence that children and young people involved with Oranga Tamariki are more likely to have greater mental health and wellbeing needs and higher levels of psychological distress than those who have never been involved with Oranga Tamariki.8 The mental health assessment also states that “lack of reliable data on needs and effectiveness of services is a system issue but is particularly lacking for children and young people involved with Oranga Tamariki.9

In the Kaitiakitanga outcome section of this report, we discuss insights from our monitoring around supporting the health needs of tamariki and rangatahi in care. This includes discussion on access to health services and supports.

In our report into the experiences of accessing primary health services and dental care, we discuss implementation of the relating to health.

Rapid review of residences In June 2023, the Chief Executive of Oranga Tamariki announced a review of secure residences in response to allegations of staff acting inappropriately in youth justice and care and protection residences. The rapid review was released in September 2023 and recommended that eight elements of the residential operating model require improvement in the near-term. In its response to the rapid review, Oranga Tamariki noted that a reporting line set up to support the review had received 46 complaints or allegations involving staff potentially causing harm to young people in care. The complaints included inappropriate language, supplying contraband, as well as more serious allegations of physical and sexual assault, and Oranga Tamariki noted all were unacceptable. Findings from these complaints add to the overall increase of findings of abuse for tamariki and rangatahi in secure residences, as detailed in our chapter on Aroha.

Under our expanded mandate, which came into effect on 1 May 2023 with the Oversight of Oranga Tamariki System Act 2022, we have begun monitoring of residences. While this report does not include residential settings, due to the timing of when this expanded mandate came into effect, our future reports will include findings from our monitoring of residences.

Cyclone Gabrielle

In February 2023, cyclone Gabrielle devastated parts of the North Island. The social and economic impacts are long-lasting, and include severe disruption to the lives of tamariki, rangatahi, whānau, caregivers and kaimahi. Their wellbeing, and that of the communities around them, is most important. We were unable to carry out some of our scheduled monitoring visits as a result. Our monitoring of the Hawke’s Bay was postponed and truncated. Our heartfelt thanks go out to the tamariki, rangatahi, whānau, caregivers and kaimahi who shared their experiences with us under such difficult circumstances.

1 Ministry of Corrections, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand Police and Oranga Tamariki.

2 https://aroturuki.govt.nz/reports/returning-home-from-care/

3 https://orangatamarikiactionplan.govt.nz/otap-resources/publications/

4 Children’s agencies are defined in legislation as the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Social Development, Oranga Tamariki and New Zealand Police.

5 Oranga Tamariki Action Plan – Report on Initial Implementation, May 2023.

6 Primary Health Needs of Children and Young People in Care: Oranga Tamariki Action Plan In-Depth Needs Assessment Report, June 2023, page 4.

7 Primary Health Needs of Children and Young People in Care: Oranga Tamariki Action Plan In-Depth Needs Assessment Report, June 2023, page 4.

8 Mental health and wellbeing needs of children and young people involved with Oranga Tamariki: Oranga Tamariki Action Plan, May 2023, page 23.

9 Mental health and wellbeing needs of children and young people involved with Oranga Tamariki: Oranga Tamariki Action Plan, May 2023, page 53.